Medida sin interacción

Fuente: entrada basada en el artículo:

![]() P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Visión cuántica en la oscuridad, Investigación y Ciencia, Temas 10, pp. 91-97.

P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Visión cuántica en la oscuridad, Investigación y Ciencia, Temas 10, pp. 91-97.

![]() P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Quantum seeing in the dark, Scientific American, Nov. 1996, p. 52, DOI: 10.1038/SCIENTIFICAMERICAN1196-72 1 (y desde Semantic Scholar).

P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Quantum seeing in the dark, Scientific American, Nov. 1996, p. 52, DOI: 10.1038/SCIENTIFICAMERICAN1196-72 1 (y desde Semantic Scholar).

![]() P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter, T. Herzog, A. Zeilinger and M.A. Kasevich, Interaction-free measurement, Physical Review Letters 74 (1995) 4763.

P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter, T. Herzog, A. Zeilinger and M.A. Kasevich, Interaction-free measurement, Physical Review Letters 74 (1995) 4763.

![]() ¿Es posible detectar la presencia de un objeto «sin que se produzca una interacción con él»? (es decir, sin hacer colisionar con él al menos un cuanto de energía: esta terminología, usual en el campo, es bastante discutible y problemática).

¿Es posible detectar la presencia de un objeto «sin que se produzca una interacción con él»? (es decir, sin hacer colisionar con él al menos un cuanto de energía: esta terminología, usual en el campo, es bastante discutible y problemática).

![]() En 1993, A. Elitzur y L. Vaidman propusieron el siguiente problema:

En 1993, A. Elitzur y L. Vaidman propusieron el siguiente problema:

¿cómo saber si hay una bomba oculta, que detona con la mínima interacción, sin arriesgarse a su explosión?

-o, con menos dramatismo:

¿cómo averiguar si hay una piedra en un camino sin tropezar con ella?

![]() A. C. Elitzur and L. Vaidman, Foundations of Physics 23 (1993) 987.

A. C. Elitzur and L. Vaidman, Foundations of Physics 23 (1993) 987.

![]() L. Vaidman: Interaction-free measurements (1996) arXiv:quant-ph/9610033; The meaning of The Interaction-Free measurements (2001), arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0103081; The Elitzur-Vaidman Interaction-Free Measurements (2008), arxiv.org/abs/0801.2777.

L. Vaidman: Interaction-free measurements (1996) arXiv:quant-ph/9610033; The meaning of The Interaction-Free measurements (2001), arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0103081; The Elitzur-Vaidman Interaction-Free Measurements (2008), arxiv.org/abs/0801.2777.

![]() R.H. Dicke, Interaction‐free quantum measurements: A paradox?, American Journal of Physics, 49 (1981) 925.

R.H. Dicke, Interaction‐free quantum measurements: A paradox?, American Journal of Physics, 49 (1981) 925.

![]() A.G. White, J.R. Mitchell, O. Nairz and P.G. Kwiat, Interaction free-Imaging, arxiv.org/pdf/quant-ph/9803060v2.pdf

A.G. White, J.R. Mitchell, O. Nairz and P.G. Kwiat, Interaction free-Imaging, arxiv.org/pdf/quant-ph/9803060v2.pdf

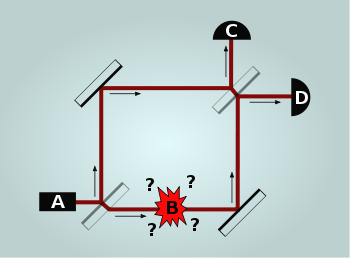

![]() Recordemos el montaje de la doble rendija a la Mach-Zehnder:

Recordemos el montaje de la doble rendija a la Mach-Zehnder:

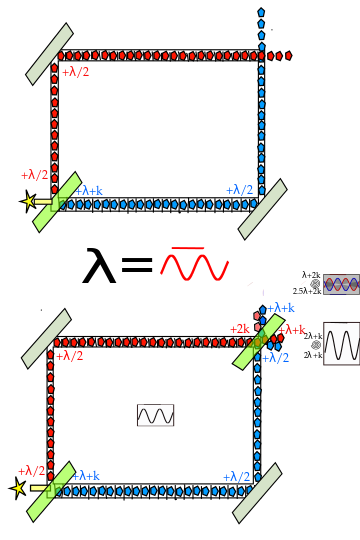

El montaje equivale a la doble rendija: además, ajustando convenientemente la fase entre los caminos ópticos, con interferencias (caminos indistinguibles, «dos caminos»), puede conseguirse que sólo 1 detector específico señale (siempre el mismo, el D-Luz; al otro detector, el D-oscuridad, nunca llega señal); con detección de camino (sin segundo divisor: caminos distinguibles, «un camino»), la luz alcanza los dos, al 50% aleatorio, nunca a la vez (también fotón a fotón).

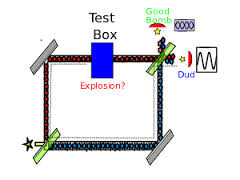

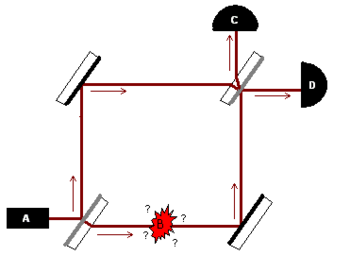

-Supongamos ahora que en el montaje interferencial, con los dos divisores de haz presentes y en acción, un obstáculo se interpone en uno de los dos caminos o brazos del interferómetro:

Con el obstáculo interpuesto, los caminos son distinguibles: por tanto, el fotón «elige sólo uno de los dos caminos» (¡se trata sólo de un RELATO!) y no se producen interferencias.

-En el 50% de los casos, el fotón elige el camino de la piedra y tropieza (la bomba explota), no llegando a ningún detector: no útil.

-En el otro 50%, la mitad de las veces el fotón elige el camino sin obstáculos, y, puesto que ya no hay interferencias, al tener caminos distinguibles, el segundo divisor lo manda, aleatoriamente, a uno de los dos detectores (25% para cada uno del total).

-Si va al detector-luz, el procedimiento no es útil: habría llegado a él también sin obstáculo.

Pero en el 25% de los casos restantes, en que el fotón llega al detector-oscuridad, habiendo ido por el camino despejado, entonces sabemos, ¡sin interacción alguna!, que había un obstáculo en el camino.

![]() Un experimento realizado:

Un experimento realizado:

![]() P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter, T. Herzog and A. Zeilinger, Interaction-Free Measurement, Phys. Rev. Lett. 74 (1995) 4763.

P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter, T. Herzog and A. Zeilinger, Interaction-Free Measurement, Phys. Rev. Lett. 74 (1995) 4763.

-Nota: Se consigue pasar del 25%, hasta un 50%, usando un divisor sin apenas reflexión, haciendo intervenir el «efecto Zenón cuántico»,

![]() Experimento de efecto Zenón con iones de berilio: W.M. Itano, D.J. Heinzen, J.J. Bollinger and D.J. Wineland, Quantum Zeno effect, Physical Review A41-5 (1990) 2295-2300: https://tf.nist.gov/general/pdf/858.pdf.

Experimento de efecto Zenón con iones de berilio: W.M. Itano, D.J. Heinzen, J.J. Bollinger and D.J. Wineland, Quantum Zeno effect, Physical Review A41-5 (1990) 2295-2300: https://tf.nist.gov/general/pdf/858.pdf.

![]() La medición afecta al resultado, de modo que un sistema cuántico puede quedar atrapado en su estado inicial, aun cuando dejado a su aire hubiera evolucionado hacia otro; véase también de nuevo:

La medición afecta al resultado, de modo que un sistema cuántico puede quedar atrapado en su estado inicial, aun cuando dejado a su aire hubiera evolucionado hacia otro; véase también de nuevo:

![]() P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Visión cuántica en la oscuridad, Investigación y Ciencia, Temas 10, pp. 91-97; versión americana: P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Quantum seeing in the dark, Scientific American, Nov. 1996, p. 52, DOI: 10.1038/SCIENTIFICAMERICAN1196-72 1 (y desde Semantic Scholar).

P. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Visión cuántica en la oscuridad, Investigación y Ciencia, Temas 10, pp. 91-97; versión americana: P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Quantum seeing in the dark, Scientific American, Nov. 1996, p. 52, DOI: 10.1038/SCIENTIFICAMERICAN1196-72 1 (y desde Semantic Scholar).

![]() Aplicaciones:

Aplicaciones:

–Fotografías sin exponer los objetos a la luz:

(¿radiografías sin irradiar a los pacientes?… ¡improbable por las involucradas!).

![]() A.G. White, J.R. Mitchell, O. Nairz and P.G. Kwiat: «Interaction-free» imaging: Phys. Rev. A 58 (1998) 605-613.

A.G. White, J.R. Mitchell, O. Nairz and P.G. Kwiat: «Interaction-free» imaging: Phys. Rev. A 58 (1998) 605-613.

![]() Abstract: Using the complementary wavelike and particle-like natures of photons, it is possible to make «interaction-free» measurements where the presence of an object can be determined with no photons being absorbed. We investigated several «interaction-free» ‘imaging’ systems, i.e., systems that allow optical imaging of photosensitive objects with less than the classically expected amount of light being absorbed or scattered by the object. With the most promising system, we obtained high-resolution (10-

Abstract: Using the complementary wavelike and particle-like natures of photons, it is possible to make «interaction-free» measurements where the presence of an object can be determined with no photons being absorbed. We investigated several «interaction-free» ‘imaging’ systems, i.e., systems that allow optical imaging of photosensitive objects with less than the classically expected amount of light being absorbed or scattered by the object. With the most promising system, we obtained high-resolution (10-m), one-dimensional profiles of a variety of objects (human hair, glass and metal wires, and cloth fibers) by raster scanning each object through the system. We discuss possible applications and the present and future limits for interaction-free imaging.

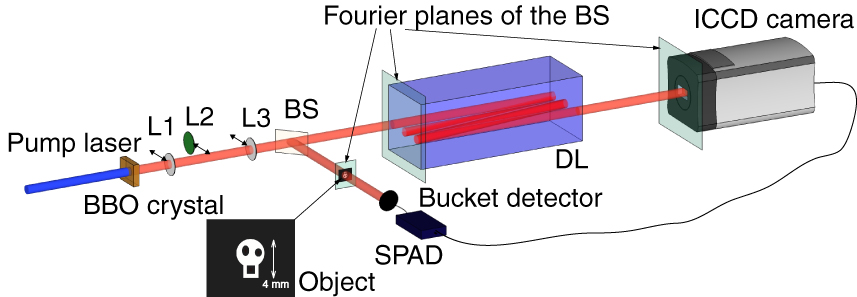

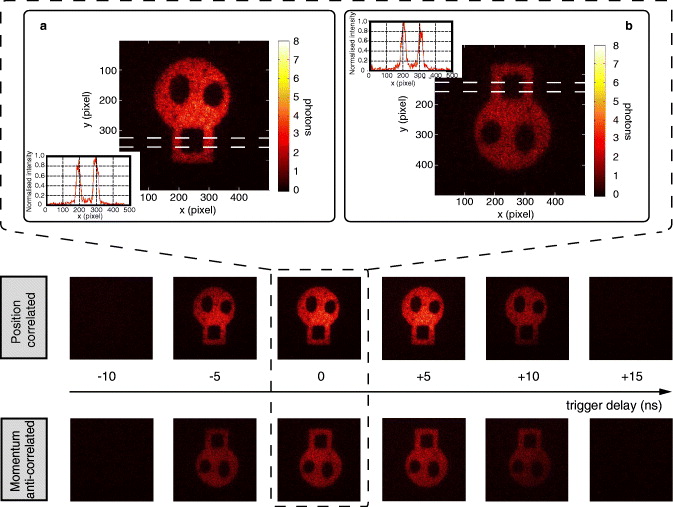

![]() R.S. Aspden, D.S. Tasca, R.W. Boyd and M.J. Padgett: EPR-based ghost imaging using a single-photon-sensitive camera ; New Journal of Physics (open access):

R.S. Aspden, D.S. Tasca, R.W. Boyd and M.J. Padgett: EPR-based ghost imaging using a single-photon-sensitive camera ; New Journal of Physics (open access):

![]() Abstract: Correlated photon imaging, popularly known as ghost imaging, is a technique whereby an image is formed from light that has never interacted with the object. In ghost imaging experiments, two correlated light fields are produced. One of these fields illuminates the object, and the other field is measured by a spatially resolving detector. In the quantum regime, these correlated light fields are produced by entangled photons created by spontaneous parametric down-conversion. To date, all correlated photon ghost imaging experiments have scanned a single-pixel detector through the field of view to obtain spatial information. However, scanning leads to poor sampling efficiency, which scales inversely with the number of pixels, N, in the image. In this work, we overcome this limitation by using a time-gated camera to record the single-photon events across the full scene. We obtain high-contrast images, 90%, in either the image plane or the far field of the photon pair source, taking advantage of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-like correlations in position and momentum of the photon pairs. Our images contain a large number of modes, >500, creating opportunities in low-light-level imaging and in quantum information processing.

Abstract: Correlated photon imaging, popularly known as ghost imaging, is a technique whereby an image is formed from light that has never interacted with the object. In ghost imaging experiments, two correlated light fields are produced. One of these fields illuminates the object, and the other field is measured by a spatially resolving detector. In the quantum regime, these correlated light fields are produced by entangled photons created by spontaneous parametric down-conversion. To date, all correlated photon ghost imaging experiments have scanned a single-pixel detector through the field of view to obtain spatial information. However, scanning leads to poor sampling efficiency, which scales inversely with the number of pixels, N, in the image. In this work, we overcome this limitation by using a time-gated camera to record the single-photon events across the full scene. We obtain high-contrast images, 90%, in either the image plane or the far field of the photon pair source, taking advantage of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-like correlations in position and momentum of the photon pairs. Our images contain a large number of modes, >500, creating opportunities in low-light-level imaging and in quantum information processing.

![]() Imágenes sacadas de la referencia:

Imágenes sacadas de la referencia:

Bibliografía

![]() P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Visión cuántica en la oscuridad, Investigación y Ciencia, Temas 10, pp. 91-97.

P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Visión cuántica en la oscuridad, Investigación y Ciencia, Temas 10, pp. 91-97.

![]() P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Quantum seeing in the dark, Scientific American, Nov. 1996, p. 52, DOI: 10.1038/SCIENTIFICAMERICAN1196-72 1 (y desde Semantic Scholar<

P.G. Kwiat, H. Weinfurter y A. Zeilinger, Quantum seeing in the dark, Scientific American, Nov. 1996, p. 52, DOI: 10.1038/SCIENTIFICAMERICAN1196-72 1 (y desde Semantic Scholar<

![]() Una divulgación completa: http://eltamiz.com/2010/07/21/cuantica-sin-formulas-el-detector-de-bombas-de-elitzur-vaidman/

Una divulgación completa: http://eltamiz.com/2010/07/21/cuantica-sin-formulas-el-detector-de-bombas-de-elitzur-vaidman/

![]() Artículo en la Wikipedia en español: Detector de bombas de Elitzur-Vaidman

Artículo en la Wikipedia en español: Detector de bombas de Elitzur-Vaidman

Dejar una contestacion